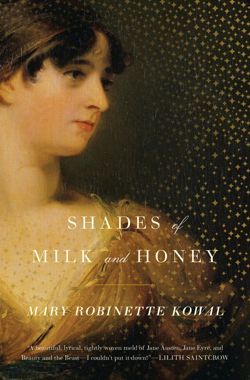

I have a confession to make: Although I’ve seen several of the film adaptations, I’ve never actually read a Jane Austen novel. So I’m taking it on faith that Mary Robinette Kowal’s Shades of Milk and Honey, one of the six books on this year’s Nebula “Best Novel” shortlist, is (to quote the flap copy) “precisely the sort of tale we would expect from Jane Austen . . . if she lived in a world where magic worked.” On the other hand, I have read a ton of Patrick O’Brian, so I can tell you that the voice of Kowal’s narration, and her character’s dialogue, does feel like an authentic simulation of an early 19th-century prose style with just enough goosing for modern readers.

It’s also a fine example of a romance novel where the romance progresses largely by deflection. And I’m not talking about the magic.

The only significant difference between the world of Shades of Milk and Honey and our own Regency England is the existence of various forms of spellcraft, including the use of “glamour” to throw a layer of illusion over ordinary reality by manipulating ethereal folds to various effects. Young women of respectable English society, such as our protagonist, Jane Ellsworth, are expected to acquire a skill with glamour; as her neighbor, Mr. Dunkirk, tells her,

“Music and the other womanly arts are what brings comfort to a home . . . Other men might seek a lovely face, but I should think they would consider exquisite taste the higher treasure.”

Jane might take some comfort in this, but she does not: She suspects that her younger, more attractive sister has already formed an attachment to Mr. Dunkirk—although they do not have an understanding—and she willingly pushes herself into the background.

Glamour plays an integral part in the social maneuverings that drive the novel’s plot, particularly with the arrival of Mr. Vincent, who has been hired by Lady FitzCameron, another of the Ellsworths’ neighbors, to create an elaborate “glamural” for her dining hall. “The illusion teazed the spectators with scents of wildflowers and the spicy fragrance of ferns,” Kowal writes of Jane’s first glimpse of Mr. Vincent’s work. “Just out of sight, a brook babbled. Jane looked for the folds which evoked it, and gasped with wonder at their intricacy.”

The descriptions are not entirely dissimilar to our contemporary concept of augmented reality, and the intense debates between Jane and Mr. Vincent about the fundamental principles of glamour’s art that follow give the story’s magic an almost science-fictional underpinning.

We can assume from the start that Jane will be rescued from spinsterhood, and yet for much of the novel it seems—deceptively so—that very little is occurring to bring this happy result about. Most of the excitement seems to be generated around Melody, who is becomingly increasingly provocative, or Mr. Dunkirk’s younger sister, Beth, who may be repeating the tragedy of her mysterious past.

Jane is primarily an observer to these developments, or else she agonizes about the deterioration of her relationship with her sister; when her own life might flare into emotional intensity, she never allows herself to get caught up in the possibility of passion. The romance, when it comes, sneaks up on Jane and then, save for one passionate (but still somewhat oblique) outburst of feeling, fades into the background until the final scene. Some readers might complain Jane’s romance doesn’t so much unfold as it’s imposed on the storyline, but I rather think Kowal’s consistent indirection is the entire point. A subtly humorous passage from early in the book is typical of the ways her characters wear social convention like a cloak:

“The Ellsworths welcomed the Dunkirks warmly and began the conversation with such simple forms as the weather, both how it had been and how they thought it would be. Then they turned to discussing how it had been the year previous and comparing that to the present weather for Miss Dunkirk’s benefit so that she might understand what luck she had with the fairness of the weather for her visit.”

Under such circumstances, direct discussion of one’s feelings, or even of the feelings of others, becomes unbearably fraught with tension. Readers more familiar with the early 19th-century social drama than I am will have to chime in on whether this is a true reflection of the genre; as I mentioned before, the language feels like an accurate pastiche of an Austenian voice, but through my own fault I have no direct experience by which to judge.

We are accustomed, I think, in today’s romances (historical or contemporary) to find heroes and heroines who spend a great deal of time, and words, fully expressing their emotional states of minds to themselves and to each other. This sort of explicit conversation is not absent from Shades of Milk and Honey, but Kowal uses it reservedly, for precise, controlled effect. Instead of a breathless romance, she has given us a carefully wrought novel about opening oneself to passion.

Previously: N.K. Jemisin’s The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, M.K. Hobson’s The Native Star

This article and its ensuing discussion originally appeared on romance site Heroes & Heartbreakers.

Ron Hogan is the founding curator of Beatrice.com, one of the first websites to focus on books and authors, and the master of ceremonies for Lady Jane’s Salon, a monthly reading series in New York City for romance authors and their fans. (Disclosure: N.K. Jemisin read from The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms at Lady Jane’s Salon.)